Warhol's Many Maos

Tucked away in some gallery of the Columbia Museum of Art, granted by anonymous doner, hangs 20 eyes. I sat in front of this jury for some time as I saw the ignorant regard everything else; they had no idea of these faces’ monetary value. The work is not listed on the museum’s website. Ah, well, what could be said about the people of South Carolina that hasn’t been said already? Likely one of the greatest American artworks, and one of the first among a series of Warhol Maos, Mao from 1972 is a good meditation on Warhol and on the way that meaning can be layered in subtle changes in composition.

.jpg)

Let’s take a look at the original Mao portrait that Warhol’s work is based off of. It is his official government portrait from 1959. Within such a black and white photograph, the way the light is cast, as well as the detail of the photo itself allow for many interpretable details. The expression he gives is complex, and already, even before its tenfold reproduction, within it lies the potential for numerous emotions. The first one that leaps out is a kind of accusatory repose. The man has nothing to prove, and he knows it because it’s already been proven. There is a kind of aural smile, not done with the lips or even the eyes. He frowns slightly, but one can see that the wrinkles of his upper cheeks are slightly scrunched- the nascence of a smile. He stands straight up, but not in an overbearing way. Indeed his head is slightly slouched, as if the viewer weren’t important enough for the main portrayed to make the kind of effort stand completely straight. The eyes are piercing; their slight rightward askance portrays a subtle recognition, maybe a knowledge of the viewers inadequacies. The texture of the skin and its sheen almost give the impression that the dirt and grime from years of grueling guerilla warfare have not yet been washed away. In this portrait is a man and a nation, their confidence assured by what has been done and what is being done, with a grit that looks towards the future, but with a relaxation that might as well claim it has already been done. It is a portrait that sits somewhere in between amiability, aloofness, and accusation; in between repose, redoubt, and resolve.

When we look at the painted copy— which is in color and is the work directly used by Warhol— we can see that some things have been altered from the photograph. As an aside, it is somewhat difficult to know with certainty exactly which portrait of Mao Warhol chose for his work, but I am using the above for a certain reason. Namely, that in other painted copies of the original photograph, Mao’s dimensions were sometimes slightly altered. This painting matches with that of Warhol’s in that Mao’s head here is thinner and longer than in the original photograph, while in others Mao’s head either matches with the dimension of the photo or is slightly taller AND wider. Notably, in this copy, a lot of the wrinkles and blemishes from the original photo are excised in part by a manipulation of light, which shines here much more evenly across the face. Because of this, the copy feels a bit more accusatory than the original, given that the cheek-smile has reduced. Moreover, Mao has been slightly rotated to lean left, which gives the copy a more domineering vibe, as if he was looking over you. Note that in the original he stands perfectly straight. However, the original factor of repose remains, just more quietly, in that the eyebrows remain slightly lifted in expression. This produces a somewhat friendly feeling for reasons that are hard to articulate, but note the difference in that if his eyebrows were furrowed the painting would obviously feel more accusatory, and if the eyebrows were even slightly more lifted it would communicate something like surprise or unease. The eyebrows here are of the way in which one exhausted but satisfied friend greets another. This effect is less pronounced in the copy, though, as a result of the treatment of the eyes, notably that the right eye has been altered to show the whites, which gives him a less good-natured mischievous feel. Finally, note that the mole has had its size slightly reduced and has been moved very subtly away from the bottom lip. This tracks with the elongated nature of the face which gives a taller if less sturdy notion.

Whew—a lot of words and we haven’t yet reached the actual subject matter, but this introduction has shown us a few things already. Namely, that slight differences in the way a face in positioned, arranged, and dimensioned can produce quite significant emotional impacts. It is also worth noting that the copy that Warhol used accentuates and masks certain features of the original, even while it nevertheless still contains the all the features and feelings of the original, just of a different composition. The accentuated and masked features will be drawn out in examination of similarly varying methods of composition in the Warhol reproductions below.

Looking at all ten Maos would be outside the scope of this article, but, more importantly, engaging with a just a few gives the reader the opportunity to draw their own conclusions on, in my opinion, the most inscrutable portraits.

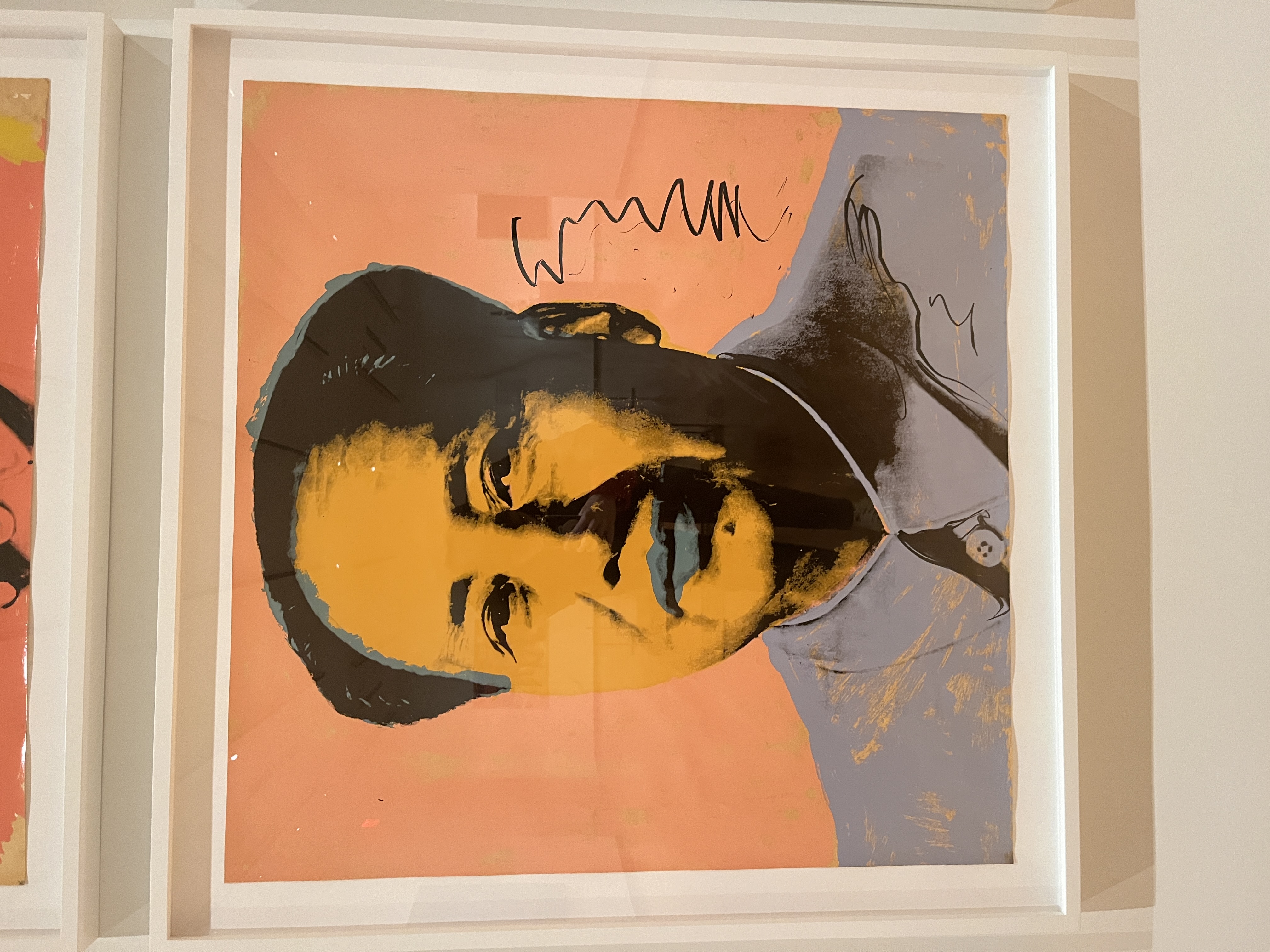

To begin, we will examine some of the differences common to all ten of Warhol’s prints from the painted portrait copy discussed above. Most notably, aside from the obvious recolorings of Mao’s skin, lips, collar, shirt, as well as the change in background color, coupled with additional varyingly placed squiggles, is that the shadows have been significantly pronounced. Mao’s face has seen a deeper blackness running along the right side of his face in all prints, as well as a darkening of the shadow on his shoulder, cast from his face. Overall, this gives Mao a leaner and starker feeling than in the original painting. Of course, though, the degree of the darkening of the shadows is dependent on the individual print.

Let’s first look at the two blue Maos on the right side of the installation, in the top right corner and on the bottom row one place from the furthest right. Beginning with the top right, Mao here is rotated slightly towards the left, which in one interpretation can again cast him as standing over the viewer. His skin is darker than the other blue Mao, giving him a softer, fuller, and more rounded feel. Notice also the shading on the left cheek, absent the other blue, about to be examined. Finally, there are two squiggles flanking both sides of his face. The other blue Mao is rotated slightly to the left, which could be called a restful state.

When I first saw the two blue Maos I felt as if the one leaning forward was mean and the one reclining was nice. Looking again, my interpretation has changed. The soft features of the forward-leaning Mao, in tandem with the squiggles on either side of his shoulder, invoking balance, and whatever color work has been done on his eyebrows, giving them a softer and even partially raised feel, makes him appear as a slightly concerned friend. On the other hand, the sharpness of the reclining Mao (indeed, it does seem as if a portion of the left side of his face has been covered by the blue of the background), his thicker eyebrows, and relatively accentuated wrinkles cast judgement. He leans into the squiggles on his right side, almost as if they whisper malfeasance.

Alternatively, look to the green Mao to the right of the bottom blue. He reclines forward in a similar manner to the Mao above him, but he, unlike his counterpart, reeks of mischief. His shirt is slightly cut off on the left side, granting a further angularity to his figure. The squiggles at his right side give the impression that something lurks behind him or is pushing him forward towards evildoing. Indeed, the slight line near his shoulder on the left side does seem as if it’s peeking out, checking the coast to see if it’s yet been caught. The most striking thing about this Mao, though, is the splotchy coloration on his face. Whereas all the other Maos wear their colors as if they were skin, the unfinished areas on green Mao offer two interpretations. One is that, in a certain sense, someone has thrown shit on him—the green that colors his face – and he glares back with a subtle knowing that says: “You will be dead before the sun rises tomorrow.” This interpretation is bolstered by several choices; the reduction of his eyes’ whites by painting over the left with green, bringing to mind a glare; the cutting off of the right eyebrow by a similar method gives his face a scrunch; the smoothing of the wrinkles alongside his mouth by the green paint reduces the previously discussed nearly invisible smile into more of a frown. Another interpretation, though, could be that the green, whatever it is that is necessary to cover his face for seeming however he wants to seem, is unfinished, and the viewer has caught him in the act of fraudulence. One gets the impression, then, that the viewer is unlikely to escape from this scenario unharmed.

A brief examination of the yellow Mao, then, at the center of the installation on the bottom row. His lips have been fully covered in blue, with an obvious frown at the left corner of his mouth. Is he scowling in displeasure, or is he amused to see me? I blink and my feelings towards him change.

Oh… the white Mao… to the left of the yellow. He.. he has no whites in his eyes. One feels that he looks off to the left, but how to know? His bright red lips are so full that they seem to rest on his face. He feels no discontent but maybe pure malice, if such a thing can be. The white of his forehead is cracked as if something were about to break through. The pink surrounds the top of his head, ready at any moment to envelop him. The squiggles… they’re so complex, are they of a foreign language? But I can’t read what they say! If only I could, maybe I would know where to run. Wait! There’s something in the shadow of his shoulder, is it the key? I can’t quite make it out, though… Wait! Wait! The mole! There’s been something inscribed on the mole. Can’t read that either… Ah, well, I’ll see it in my dreams, taunting me, promising a truth inaccessible, impossible. And, yes, there’s that little finger reaching in from the bottom of the frame, perhaps motioning me, perhaps mocking me for my iniquity.

And what are we left with? I can’t speak for you, dear reader, but I am thoroughly disquieted. Here I sit; will a slight forward incline make me threatening to those around me? Can the tiny details of my cheek muscles reveal subconscious desires and feelings? And what if the whites of my eyes were to black out in my sleep?